What bioavailability studies actually measure

When a generic drug company wants FDA approval, they don’t need to repeat every clinical trial the brand-name drug went through. Instead, they run bioavailability studies - simple, controlled tests that answer one critical question: Does the generic drug get into your bloodstream the same way as the brand?

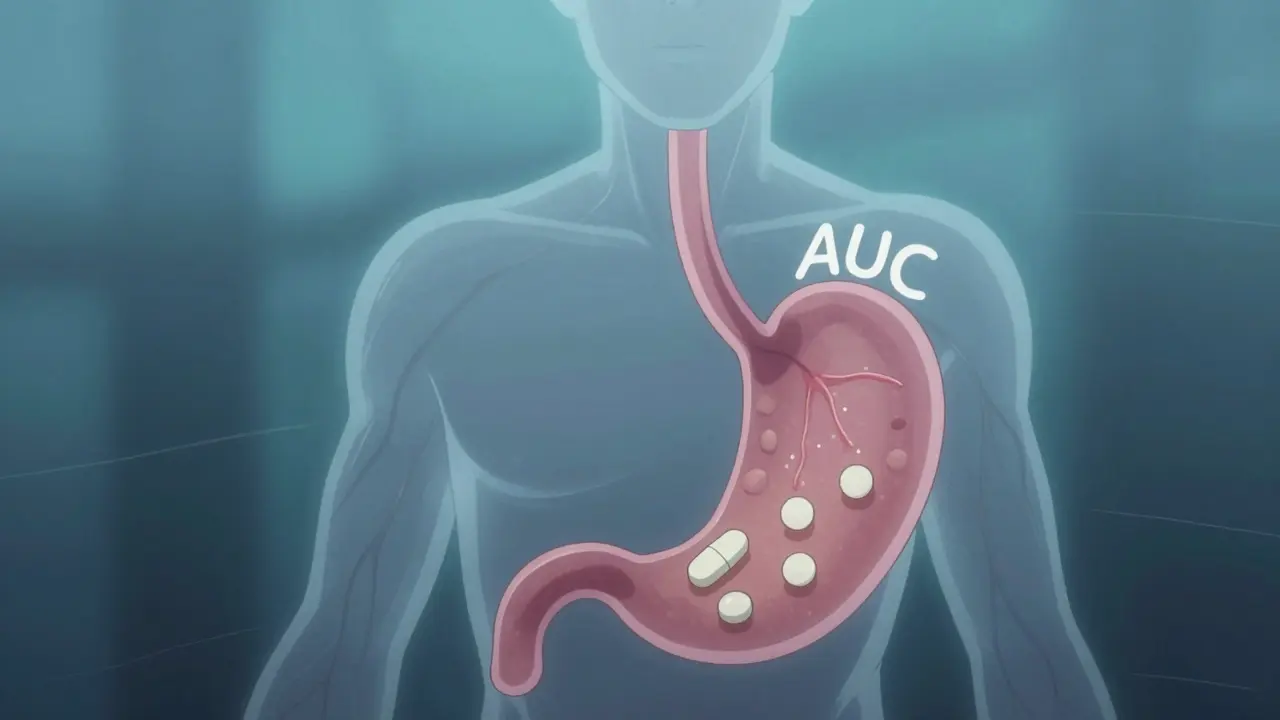

These studies don’t look at whether the drug cures your condition. They look at how fast and how much of the active ingredient enters your blood. That’s called bioavailability. It’s measured using two key numbers: AUC and Cmax.

AUC - Area Under the Curve - tells you the total amount of drug your body absorbs over time. Think of it like the total rainfall in a day. Cmax - the maximum concentration - tells you how high the drug spikes in your blood, like the peak of that rainfall. Both matter. A drug might hit the same peak but take longer to get there, or vice versa. That’s why both values are checked.

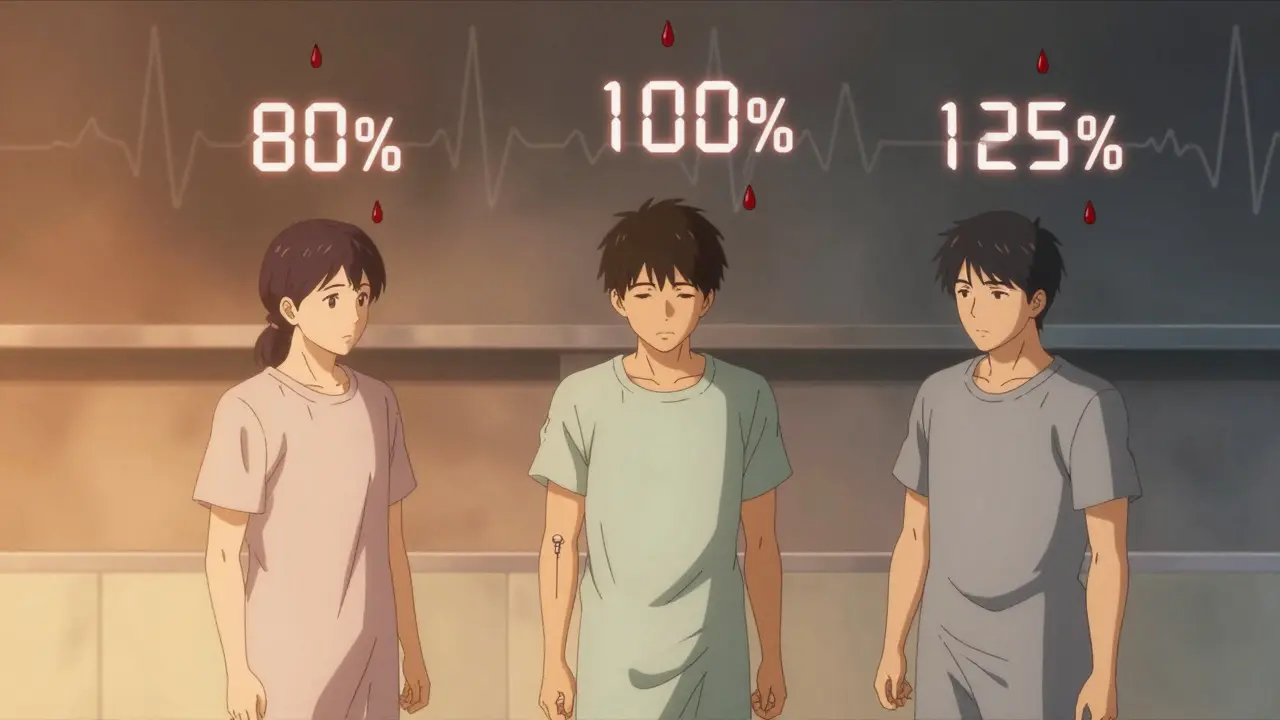

Here’s how it works: Healthy volunteers take the generic drug, then the brand-name version, usually weeks apart. Blood is drawn every 15 to 60 minutes for up to 72 hours. Labs measure how much drug is in each sample. The data is plotted into curves. If the curves look nearly identical, the generic passes.

Why the 80-125% range is the rule

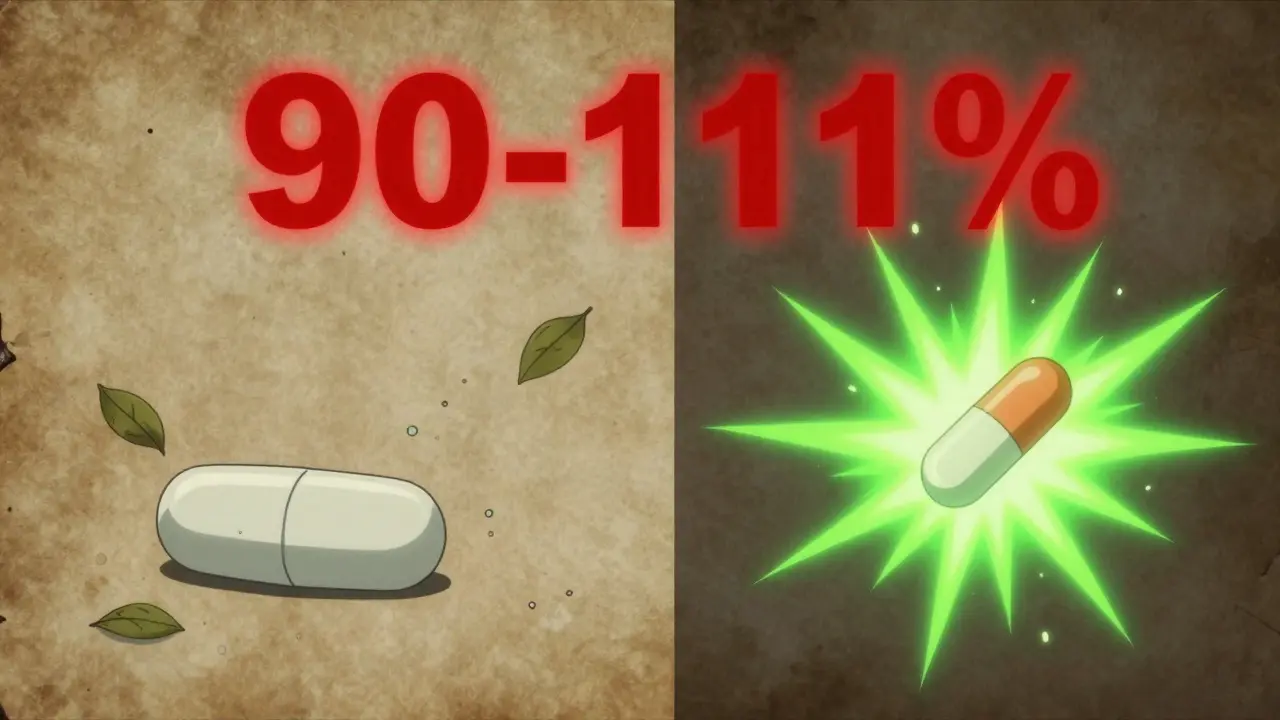

The FDA doesn’t require the generic to be exactly the same. It allows a range: the 90% confidence interval for AUC and Cmax must fall between 80% and 125% of the brand-name drug’s values. That means the generic can be 20% lower or 25% higher and still be approved.

That range isn’t pulled out of thin air. It’s based on decades of clinical data showing that differences within this range rarely affect how well a drug works or how safe it is. For most medicines, a 20% change in blood levels doesn’t change outcomes. A study of over 15,000 generic approvals since 1984 found no documented cases where bioequivalence limits alone caused a treatment failure.

But there are exceptions. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin, digoxin, or levothyroxine - even small changes can be dangerous. For those, the acceptable range is tighter: 90% to 111%. The FDA knows these drugs need more precision. That’s why you’ll often see warnings on prescriptions for these generics: "Do not substitute without consulting your doctor."

How the studies are designed

Most bioequivalence studies use a crossover design. Each volunteer takes the brand-name drug in one period, then the generic in another, with a washout period in between - usually five times the drug’s half-life. This ensures no leftover drug from the first dose interferes with the second.

Typical studies involve 24 to 36 healthy adults. That’s enough to detect meaningful differences with statistical confidence. The volunteers aren’t patients - they’re chosen for good health to avoid complications from other conditions.

The testing environment is tightly controlled. Volunteers fast overnight. They take the drug with a glass of water. No caffeine, no alcohol, no other medications. Blood samples are handled with extreme care. If the drug breaks down easily, it’s kept cold, tested immediately, or stabilized with chemicals.

For complex drugs - like extended-release pills, inhalers, or topical gels - the rules get more detailed. An extended-release pill must match the brand not just in overall absorption but also in how slowly it releases the drug over time. That means multiple AUC measurements at different intervals: early, middle, and late. For topical products, where little drug enters the blood, scientists may measure skin response instead - like how much a cream reduces redness.

When bioequivalence studies aren’t needed

Not every generic needs a blood test. The FDA allows waivers under the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). If a drug is highly soluble and highly permeable (BCS Class 1), and the generic matches the brand in ingredients and dissolution rate, the FDA may approve it without human studies.

Drugs like metformin, atenolol, and ranitidine often qualify. These are well-understood, stable, and easily absorbed. The same applies to some BCS Class 3 drugs - highly soluble but less permeable - if the formulation is nearly identical.

This saves time and money. It also reduces the number of healthy volunteers needed. But it’s only allowed for simple, well-characterized drugs. For anything complex - modified-release, suspensions, or drugs with poor solubility - the FDA still requires full in vivo testing.

What happens when a generic fails

Failures aren’t common, but they happen. One study showed a generic with an AUC ratio of 1.16 - 16% higher than the brand. At first glance, that sounds fine. But the 90% confidence interval went up to 1.30. That’s above the 1.25 limit. The product was rejected.

Another case: a generic had an AUC ratio of 0.90 - 10% lower. That’s within range. But the Cmax ratio was 0.75 - 25% lower. That’s outside the 80% lower limit. Even if total exposure was okay, the peak was too low. That could mean slower pain relief or reduced effectiveness.

When a product fails, the company must fix the formulation. That might mean changing the particle size, adding a different coating, or adjusting the manufacturing process. Sometimes, it’s as simple as switching the binder. Other times, it’s a complete redesign.

And sometimes, the brand-name company holds patents that block generics from matching the exact formulation. That’s why some generics look different - different color, shape, or size - even though they work the same.

Are there real-world concerns?

Most patients can’t tell the difference between brand and generic. The FDA says 90% of people report no change in effectiveness. But there are reports - mostly from patients with epilepsy, thyroid disease, or heart conditions - that switching caused problems.

The Epilepsy Foundation tracked 187 cases between 2020 and 2023 where seizure frequency increased after switching to a generic. The FDA investigated and found only 12 of those cases (6.4%) were possibly linked to bioequivalence issues. The rest were due to missed doses, stress, or other factors.

Some doctors, like cardiologist Dr. Michael Chen, have seen rare cases where patients developed palpitations after switching from brand to generic amlodipine. All symptoms reversed when they switched back. But in his practice of 3,000 patients, that’s fewer than one in a thousand.

The science still holds. For the vast majority, generics are just as safe and effective. But for a small number of patients with sensitive conditions, consistency matters. That’s why many doctors recommend sticking with the same generic brand - or even the original brand - if it’s working.

The future of bioequivalence testing

The FDA is exploring new ways to prove equivalence without always testing people. One promising area is artificial intelligence. In 2023, the FDA partnered with MIT to train algorithms on over 150 drug compounds. The AI predicted AUC ratios with 87% accuracy based only on formulation data - no human subjects needed.

Another advance is model-informed drug development (MIDD). Instead of running full studies, companies can use computer simulations to predict how a new formulation will behave. If the model is validated, it can replace part of the clinical trial.

For highly variable drugs - like tacrolimus - the FDA now uses scaled bioequivalence. If the brand drug varies a lot between people, the acceptable range widens to 75-133%. This avoids rejecting good generics just because the brand itself is unpredictable.

Still, for now, blood tests remain the gold standard. Nothing beats real human data when it comes to safety. Until AI or models can fully replace them, bioavailability studies will stay at the heart of every generic drug approval.

Why this matters for you

If you’re taking a generic drug, you’re likely saving money - and getting the same treatment. Bioavailability studies make that possible. They’re not just paperwork. They’re science that ensures your pills work the same way, whether they cost $5 or $50.

But if you have a condition where tiny changes matter - like seizures, thyroid imbalance, or blood thinning - talk to your doctor. Ask if your generic has passed the stricter 90-111% range. Ask if switching brands could affect you. You don’t need to avoid generics. You just need to be informed.

The system isn’t perfect. But for over 40 years, it’s kept millions of people healthy while cutting drug costs by billions. That’s not just regulation. That’s public health working as it should.

I love how this breaks down something so technical into something actually understandable. I’ve been on generics for years and never knew how much science went into making sure they’re safe. Seriously, this is public health done right.

This is all just corporate propaganda. The FDA’s been bought off. I’ve seen people have seizures after switching - and no one wants to admit it.

I had a cousin who went from brand-name levothyroxine to generic and started feeling like a zombie. She switched back and was herself again in a week. It’s wild how one tiny difference can mess with your whole life.

The BCS waiver system is genius. For drugs like metformin, the dissolution profile is so predictable that human trials are overkill. It’s smart regulation - saves time, money, and volunteers. The FDA knows what it’s doing.

I don’t trust generics. My blood pressure went haywire after switching. They’re not the same. And no, I don’t care what the FDA says. My body knows.

This is an excellent overview. The 80-125% range is grounded in pharmacokinetic principles and decades of clinical observation. It’s not arbitrary - it’s evidence-based. For most drugs, the variation is clinically insignificant.

I’m a nurse and I’ve seen it firsthand - one patient went from 10 seizures a month to 30 after switching generics. The family cried. The doctor shrugged and said, ‘It’s bioequivalent.’ But bioequivalent doesn’t mean bioidentical. There’s a difference.

The application of scaled average bioequivalence (SABE) for highly variable drugs like tacrolimus represents a paradigm shift in regulatory science. By accounting for intra-subject variability, the widened confidence interval (75–133%) mitigates Type I error without compromising safety.

I read this entire thing and I’m still not convinced. The FDA is a joke. They approve everything. My cousin’s generic antidepressant made her suicidal. And they say it’s ‘within range.’ What range? The range of corporate profits?

It is indeed a remarkable feat of regulatory science, this bioequivalence framework. One cannot overstate the societal benefit conferred by the widespread adoption of generic pharmaceuticals, particularly in resource-constrained settings. The meticulousness of the methodology is truly commendable.

AMERICA MADE THE BEST DRUGS. WHY ARE WE LETTING INDIAN COMPANIES MAKE OUR MEDS?!?!?!!? The FDA is letting foreign labs cut corners. 80-125%?! That’s a 45% window!! I bet 90% of these generics are made in moldy factories with untrained workers. #MakeGenericsGreatAgain 🇺🇸💊🔥

This is the kind of stuff that makes me love science. They’re not just guessing - they’re plotting curves, measuring peaks, tracking how fast your body drinks the medicine like it’s a soda. And if the curve looks like a twin of the brand? That’s poetry. That’s justice. That’s $5 instead of $500 for your life-saving pill. Keep this up, FDA. You’re doing god’s work.