Gut Bacteria & Drug Interaction Checker

Check Your Medication Interactions

Enter a drug name to see if your gut bacteria might affect how it works

Results

Enter a medication name to see if gut bacteria might affect it.

Ever taken a medication and had a reaction no one else seems to get? You’re not imagining it. The answer might be hiding in your gut.

The Hidden Metabolizers Inside You

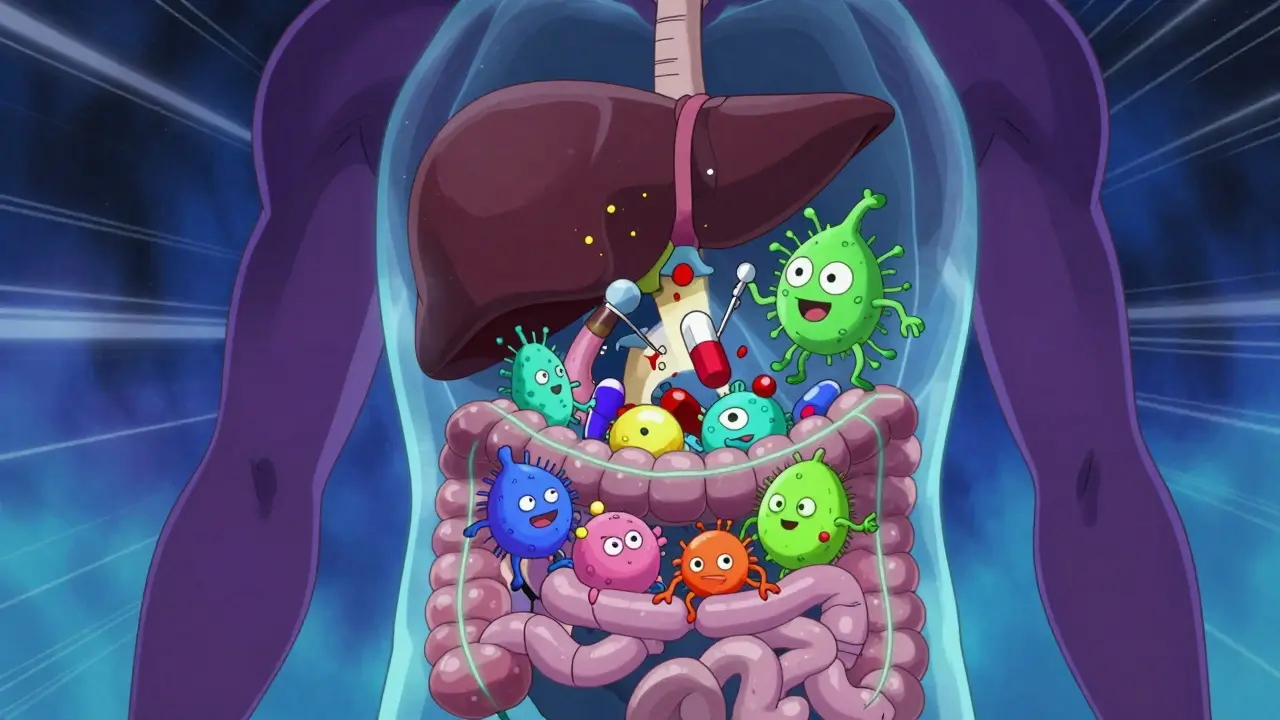

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria - more than the number of cells in your body. For decades, doctors thought these microbes just helped with digestion. Now we know they’re also tiny pharmacists. They don’t just break down your food. They break down your drugs.When you swallow a pill, most of it passes through your stomach and small intestine unchanged. But once it hits your colon - where bacterial density hits 1011 to 1012 CFU/mL - the real transformation begins. These microbes have enzymes that can chemically alter drugs in ways your liver never could. Some turn harmless compounds into toxins. Others deactivate life-saving medications before they even reach their target.

This isn’t theory. In a landmark 2019 study from Yale, researchers found that gut bacteria were responsible for 20% to 80% of toxic drug metabolites circulating in the blood. That means for some patients, the side effects they suffer aren’t because the drug is flawed - it’s because their gut microbes are turning it into something dangerous.

When Good Drugs Turn Bad

One of the clearest examples is irinotecan, a chemotherapy drug used for colorectal cancer. After your liver processes it, the body turns it into SN-38-glucuronide - a less toxic form meant to be safely excreted. But in the colon, certain bacteria produce an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme rips off the protective sugar group and turns it back into SN-38, a potent toxin that attacks the intestinal lining.Result? Severe, sometimes life-threatening diarrhea in 25% to 40% of patients. Studies show the severity directly matches the level of this bacterial enzyme - with a correlation of r=0.87. Patients with high levels of beta-glucuronidase-producing bacteria are far more likely to need dose reductions or hospitalization.

Then there’s digoxin, a heart medication. For most people, it works perfectly. But in about 30% of patients, it doesn’t work at all. Why? Their gut contains a specific bacterium called Eggerthella lenta, which breaks down digoxin before it can be absorbed. No bacteria? The drug works. Bacteria present? The drug is neutralized. This explains why two people on the same dose can have completely different outcomes.

Even common drugs like clonazepam (used for seizures and anxiety) behave differently depending on gut microbes. Germ-free mice showed 40% to 60% higher blood levels of the drug than mice with normal gut flora. That means people with certain microbiomes could be getting a stronger dose than intended - increasing the risk of drowsiness, dizziness, or even respiratory depression.

When the Microbiome Turns Off the Medicine

It’s not just about making drugs toxic. Sometimes, the microbiome stops them from working at all.Take prontosil, one of the first antibiotics ever developed. It doesn’t work unless gut bacteria chop it apart with an enzyme called azoreductase. Without that bacterial kickstart, the drug stays inactive. In antibiotic-treated mice, its effectiveness dropped from 90% to just 12%.

Even statins - drugs like lovastatin used to lower cholesterol - can be affected. A 2014 study found that patients on long-term antibiotics had 35% less cholesterol-lowering effect. Why? Their gut microbes, which normally help metabolize statins, were wiped out. The drug couldn’t be processed properly, leaving cholesterol levels high.

This isn’t rare. A 2023 review in Nature identified 117 drugs whose effects are changed by gut bacteria. Of those, 82% become less effective, and 18% become more toxic. That’s over a hundred medications where your gut could be the deciding factor between healing and harm.

Why This Matters for Your Health

Adverse drug reactions are a massive problem. In the U.S. alone, they send 1.3 million people to the emergency room every year. Many of these cases are labeled as “unexplained” - because doctors still assume everyone’s body processes drugs the same way.But your microbiome is unique. Just like your DNA, your gut bacteria are shaped by your diet, antibiotics, birth method, environment, and even where you live. Two people taking the same drug at the same dose can have completely different outcomes - not because one is “non-compliant” or “resistant,” but because their gut microbes are doing different things to the medicine.

That’s why researchers now call this an “emerging priority for precision medicine.” Instead of guessing the right dose, we could one day test your microbiome to predict how you’ll react to a drug - and adjust treatment before you even take it.

What’s Being Done About It

Scientists aren’t just studying this - they’re building tools to fix it.Diagnostic tests are already available. A simple stool sample can be analyzed with metagenomic sequencing to find out which drug-metabolizing genes your gut bacteria carry. These tests cost $300-$500 and are over 95% accurate for known metabolic functions. Some clinics in the U.S. and Europe now offer them for patients on high-risk drugs like chemotherapy or blood thinners.

Targeted inhibitors are in development. For example, drugs that block beta-glucuronidase are in Phase II trials. Early results show they can reduce chemotherapy-induced diarrhea by 60-70%. Imagine taking a pill alongside your chemo that stops your gut from turning the drug into poison.

Personalized probiotics are also being tested. One trial (NCT05102805) is testing engineered bacteria designed to either boost or block specific drug-metabolizing enzymes. The goal? To give patients a custom microbial “tune-up” before they start a new medication.

Pharmaceutical companies are catching on. Since 2020, Pfizer, Merck, and others have started screening new drugs for microbiome interactions during Phase I trials. It adds about $2.5 million to development costs - but could save hundreds of millions by avoiding dangerous side effects after launch.

What You Can Do Right Now

You can’t control your microbiome overnight. But you can be smarter about how you take medications.- If you’re on a drug with known side effects - especially chemotherapy, heart meds, or antidepressants - ask your doctor: “Could my gut bacteria be affecting how this works?”

- Don’t take antibiotics unless necessary. They don’t just kill bad bacteria - they wipe out the ones that help metabolize your drugs.

- Keep a symptom diary. Note when side effects start after starting a new medication. That pattern could be a clue your microbiome is involved.

- If you’ve had repeated bad reactions to a drug, consider asking for a microbiome test. It’s not routine yet, but it’s becoming more accessible.

There’s no magic diet or supplement that will “fix” your drug metabolism. But understanding the role of your gut bacteria gives you a new lens to talk to your doctor - one that moves beyond “you’re just sensitive” to “here’s what’s actually happening in your body.”

The Future Is Personal

In five to seven years, we’ll likely see microbiome testing become part of standard care for high-risk drugs. Dosing algorithms will factor in your bacterial profile. Probiotics will be prescribed alongside prescriptions. And side effects that once seemed random will become predictable - and preventable.This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening now. The NIH has poured $14.7 million into research between 2023 and 2025. The FDA and EMA now recommend microbiome testing for new cancer drugs. This field is growing at 32.1% per year - faster than most areas of medicine.

What this means for you? Your body isn’t just you. It’s a community - and that community is helping - or hindering - your treatment every day. The more we learn about it, the better we can treat you.

Can antibiotics change how my medications work?

Yes. Antibiotics can wipe out gut bacteria that help metabolize drugs - either activating them or breaking them down. For example, long-term antibiotic use can reduce the effectiveness of statins by up to 35%, or prevent prodrugs like prontosil from working at all. Even short courses can temporarily alter drug responses.

Is there a test to check if my gut bacteria affect my drugs?

Yes. Stool tests using metagenomic sequencing can identify bacterial genes linked to drug metabolism. These tests detect enzymes like beta-glucuronidase or azoreductase with over 95% accuracy. They cost $300-$500 and are becoming available through specialty clinics and research programs.

Can I change my microbiome to improve drug response?

Not yet with diet alone - but targeted approaches are in development. Fecal transplants and engineered probiotics are being tested to add or block specific drug-metabolizing bacteria. For now, avoiding unnecessary antibiotics and eating fiber-rich foods supports a healthier microbiome, which may help stabilize drug responses.

Which drugs are most affected by the microbiome?

Over 117 drugs are known to be affected. The most studied include irinotecan (chemotherapy), digoxin (heart), clonazepam (seizures), prontosil (antibiotic), and lovastatin (cholesterol). These drugs either become toxic or lose effectiveness depending on gut bacteria. New research is identifying more every year.

Why don’t doctors talk about this more?

Because it’s still emerging. Until recently, the medical field assumed drug metabolism happened only in the liver. The microbiome’s role was overlooked. Now, with new data and regulatory pressure, more doctors are learning about it - but widespread adoption will take time. If you’ve had unexplained side effects, bring it up. You might be ahead of the curve.

I had unexplained diarrhea after chemo and no one could figure it out. Turns out my gut bacteria were turning the drug toxic. Got tested and now I take a blocker with my infusion. Life changed.

Just wish more docs knew this.

The profound implications of microbial pharmacodynamics challenge the anthropocentric paradigm of drug metabolism, which has historically privileged hepatic enzymology as the sole determinant of pharmacokinetic outcomes. The human microbiome, as a symbiotic organ, necessitates a reconfiguration of therapeutic paradigms.

Big Pharma doesn't want you to know this because if your gut breaks down their drugs, they can't sell you more. They'd rather keep you sick and on pills. They've been hiding this since the 80s. Ask about the Monsanto connection.

The gut microbiota's enzymatic repertoire, particularly beta-glucuronidase and azoreductase isoforms, introduces a confounding variable in pharmacokinetic modeling. This non-genetic pharmacogenomic layer is a systemic oversight in clinical trial design. We're essentially dosing blind.

So now we're blaming bacteria for bad drugs? Next they'll say your phone gave you cancer. This is just woke science. Take your pills like a normal person and stop looking for excuses. America doesn't need microbiome consultants.

They're lying. This isn't science-it's a cover-up. The government and pharma are using gut bacteria as an excuse to avoid liability for their toxic drugs. They know the truth. They've been poisoning us with glyphosate for decades to kill the good bugs. That's why everyone's getting sick. Wake up.

So basically my 300 dollar stool test is gonna tell me why my anxiety meds make me feel like a zombie? Cool. I'll just keep taking them and blaming my colon. Thanks, science.

This is one of the most exciting frontiers in medicine I’ve seen in years. The idea that our microbial partners can modulate drug efficacy is not just fascinating-it’s transformative. Imagine a future where treatment is truly tailored, not trial-and-error. This deserves celebration, not skepticism.

Thank you for sharing this.

Of course the microbiome affects drug metabolism. Everyone with half a brain knows this. What’s surprising is that it took the medical establishment 70 years to catch up. Meanwhile, people suffered because doctors were too arrogant to look beyond the liver. Classic.

I’ve been feeling this in my soul for years. The gut is the second brain, right? And when your microbes are outta whack, your whole being suffers. I stopped antibiotics after my last flu and suddenly my antidepressants started working. It’s like my body finally remembered how to breathe.

It’s not science. It’s magic. And they’re trying to patent it.

Huh. So if I took a probiotic before my statin, would that change anything? Or is it too late?

I’ve been taking a daily probiotic for a year now. My blood pressure meds work way better. I think my gut finally got its act together 😊

India has known this for centuries. Ayurveda always treated digestion as the root of all medicine. Western science just rediscovered what our grandmothers knew. Now they want to patent it and sell it back to us for $500.

I never thought about this but it makes so much sense. My grandma took digoxin for 20 years and never had an issue. My uncle took the same dose and ended up in the hospital. Guess their guts were just different. Wild.