What an insulin allergy really looks like

Most people with diabetes expect side effects like low blood sugar or sore injection sites. But if you suddenly get swelling, itching, or hives right after injecting insulin, it might not be a normal reaction-it could be an allergy. Insulin allergies are rare, affecting only about 2.1% of people using insulin, according to the Independent Diabetes Trust. Still, they’re serious enough to stop treatment-or worse, trigger anaphylaxis if ignored.

Back in the 1920s, when insulin was first made from animal pancreases, up to 15% of users had allergic reactions. Today, with purified human and analog insulins, that number has dropped sharply. But allergies haven’t disappeared. Some people react not to the insulin molecule itself, but to additives like metacresol or zinc used to stabilize the formula. Humalog, for example, has more metacresol than other insulins, which may explain why some switch and suddenly feel better.

Local reactions: swelling, redness, and nodules

The most common insulin allergy is localized. You’ll notice redness, warmth, and itching right where you injected. Sometimes it turns into a hard, tender lump under the skin that shows up 30 minutes to 6 hours later. These nodules can last a few days but usually fade on their own in 24 to 48 hours for 85% of cases.

Don’t mistake this for poor injection technique. If you’ve been injecting the same way for months and suddenly get this reaction, especially in multiple spots, it’s likely immune-related. These reactions are often IgE-mediated, meaning your body sees insulin-or an additive-as a threat and releases histamine. That’s why antihistamines help.

But here’s the catch: some people develop delayed reactions that show up 2 to 24 hours later. These aren’t from histamine. They’re T-cell driven, causing bruising, deep swelling, or even joint pain. One patient I read about developed painful knees and wrists after 12 years of steady insulin use. No one suspected an allergy-until they stopped and restarted, and the pain came back.

Systemic reactions: when it’s an emergency

Less than 0.1% of insulin users have a full-body reaction. But when it happens, it’s life-threatening. Symptoms include hives all over the body, swelling of the lips or tongue, trouble breathing, dizziness, or a sudden drop in blood pressure. This is anaphylaxis-and you need help now.

Studies show about 40% of systemic insulin reactions progress to anaphylaxis. That’s why the NHS and other medical bodies stress: if you feel your throat closing or can’t catch your breath after an injection, call emergency services immediately. Don’t drive yourself. Don’t wait. Anaphylaxis can kill in minutes.

Many people confuse low blood sugar symptoms-shaking, sweating, anxiety-with allergies. But those are metabolic, not immune. If you’ve checked your blood sugar and it’s normal, and you’re still breaking out in hives or swelling, it’s not hypoglycemia. It’s an allergy.

How doctors diagnose it

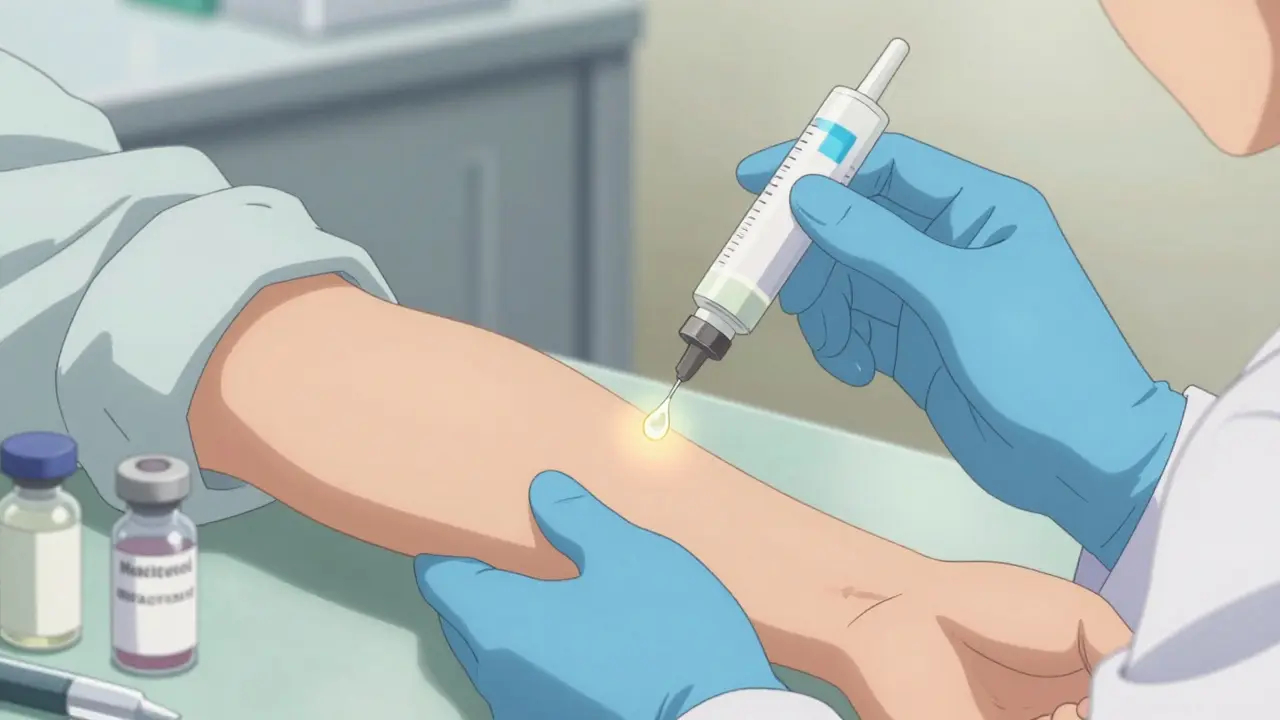

There’s no blood test that says ‘insulin allergy’ outright. Diagnosis comes from a mix of timing, symptoms, and testing. Skin prick tests or intradermal tests are the gold standard. A tiny amount of insulin is injected under the skin to see if a wheal forms. If it does, you’re likely allergic to that specific type.

But here’s the tricky part: you might be allergic to the preservatives, not the insulin. That’s why allergists test not just the insulin itself, but the solution it’s mixed in. If you react to Humalog but not Lantus, it might be the metacresol, not the insulin molecule.

For delayed reactions, patch testing is used. A small patch with insulin is taped to your skin for 48 hours. If a rash develops, it’s T-cell mediated. This matters because the treatment is different. Steroids work better than antihistamines here.

What to do if you have a reaction

First, don’t stop insulin. Stopping can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis-another life-threatening emergency. Instead, contact your diabetes team immediately. They’ll help you figure out what’s going on.

For mild local reactions, over-the-counter antihistamines like cetirizine or loratadine can help. Apply a topical calcineurin inhibitor like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus right after injecting, then again 4 to 6 hours later. This blocks the immune response at the skin level. For delayed bruising or swelling, a mid-to-high potency steroid cream like flunisolide 0.05% applied twice daily can clear it up in a week.

If you’re having repeated reactions, switching insulin types works in about 70% of cases. Try moving from a human insulin to an analog like glargine or degludec. Or switch brands entirely. Some people react to one manufacturer’s formulation but not another’s-even if the insulin is technically the same.

When desensitization is the answer

For those who can’t switch insulin-like people with type 1 diabetes who need rapid-acting insulin after meals-desensitization is the next step. It’s not easy. You’re given tiny, increasing doses of insulin under medical supervision, usually over several hours or days. The goal is to train your immune system to tolerate it.

Studies show this works in two out of three patients. One study of four patients found symptoms disappeared completely in two, and improved significantly in the other two. It’s not risk-free. You might get a reaction during the process. That’s why it’s done in a clinic with emergency meds on hand.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are making this safer. They let doctors watch your blood sugar in real time, so they can catch a drop before it becomes dangerous. This wasn’t possible a decade ago.

What doesn’t work

Some people think skipping doses or rotating injection sites will reduce reactions. It won’t. In fact, inconsistent use can make allergies worse. Your immune system gets confused and may react more strongly when insulin returns.

Also, don’t assume you’re safe just because you’ve used the same insulin for years. Delayed reactions can appear after 5, 10, even 15 years. There’s no immunity built up. Your body can change its mind.

And no, oral diabetes pills won’t fix this for everyone. Only people with type 2 diabetes have the option to switch away from insulin. Type 1 patients must use insulin to survive. Desensitization or switching formulations are the only real paths forward.

What’s next for insulin allergy treatment

Researchers are working on new insulin formulas with fewer additives. Some companies are testing versions without metacresol or zinc, aiming to reduce immunogenicity. Early results look promising.

Biomarkers are also being studied. If scientists can find a blood sign that predicts who’s likely to react, we could screen people before they even start insulin. That’s still years away-but it’s coming.

For now, the key is awareness. If you’re having unexplained skin reactions after insulin, don’t brush it off. Talk to your doctor. Get tested. Don’t wait until it turns into an emergency. Insulin is life-saving. Allergies don’t have to be a death sentence.

What to track if you suspect an allergy

- Time between injection and reaction

- Exact insulin type and brand

- Location of reaction (injection site or elsewhere)

- Severity: mild itch vs. swelling vs. breathing trouble

- Any new medications, supplements, or changes in diet

Keep this log for at least two weeks. Patterns emerge fast. One patient noticed every reaction happened after lunchtime injections of NovoRapid. Switching to Fiasp fixed it. The difference? A different preservative mix.

So let me get this straight - you're telling me I've been injecting poison for 8 years and just now it's 'allergic'? Classic. My doctor said it was 'irritation' from my fat rolls. Guess I'm just too lazy to care until my arm looked like a measles outbreak.

The evolution of insulin from bovine extracts to engineered analogs is a fascinating case study in biomedical reductionism - we've stripped away the biological complexity to the point where the very stabilizers we add become the new antigens. It's ironic: in our quest for purity, we've created a new kind of impurity. The immune system doesn't care about patents or FDA approvals - it only recognizes molecular patterns. If metacresol triggers IgE, then the molecule is the villain, regardless of whether it's labeled 'active ingredient' or 'excipient'.

I had a nodule last year after switching to Humalog. Thought I was injecting wrong. Turns out, it was the metacresol. Used tacrolimus cream after each shot and it vanished in 3 days. Seriously, if you're getting weird lumps - don't ignore it. Talk to your endo. I almost didn't and it was scary.

Stop injecting. Just stop.

So... the solution is to pay more for a different brand of poison? Sounds like pharma's greatest hit.

I'm so proud of American science. We made insulin so clean it now makes people allergic to the packaging. Next up: allergic to the syringe. We're winning.

I switched from NovoRapid to Fiasp because my arm looked like a spiderweb after every shot. Same insulin, different preservatives. Magic. Also, I cried. Not because of the pain - because I finally felt heard.

Please, please, please - if you're having a reaction, keep a log! Time, brand, location, severity - write it down. I did this for two weeks and noticed a pattern: every reaction happened after I ate carbs. Turns out, my blood sugar spikes were making the histamine release worse. It's not just the insulin - it's the combo. Talk to your team. Don't suffer in silence.

Oh wow. So the real problem isn't diabetes - it's that Big Pharma doesn't want you to know you can just use insulin from the 1980s. Animal insulin. Cheap. Effective. No metacresol. But no, we gotta make it 'premium' and now we're allergic to our own progress. America, you did it again.

Wait so if I'm allergic to the preservative not the insulin can I just dilute it with saline and inject that? Like a DIY fix?

I've been on Lantus for 12 years. Never had a reaction. Then last month - sudden hives on my thigh. No fever, no swelling, just itching. Got tested. Turned out to be a delayed T-cell response. Steroid cream worked. But here's the kicker - I'd been using the same pen for 6 months. No change in insulin. No change in routine. Just... my body changed its mind. It's wild.

The immunological mechanisms underlying insulin-induced cutaneous reactions are heterogeneous, encompassing both IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity and T-cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity. Clinical management requires stratified diagnostic protocols including intradermal skin testing and patch testing to differentiate between allergen sources - insulin molecule versus excipients such as metacresol or zinc.

In India we use animal insulin. No fancy preservatives. No allergies. You people overthink everything. Just inject and stop complaining.