When patients move between hospitals, clinics, or nursing homes, their medications often get lost in the shuffle. A pill that was stopped last week might still be on the list. A new drug might be added without checking if it clashes with something else. These mistakes aren’t rare-they happen in nearly every other transition of care. That’s where pharmacist-led substitution programs come in. These aren’t just paperwork exercises. They’re clinical interventions that save lives, cut hospital readmissions, and save money-all led by pharmacists who know drugs inside and out.

What Exactly Is a Pharmacist-Led Substitution Program?

A pharmacist-led substitution program is a structured process where pharmacists review a patient’s entire medication list, find errors or risks, and replace unsafe or unnecessary drugs with safer, more effective alternatives. This isn’t about swapping one brand for another because it’s cheaper. It’s about making clinical decisions based on the patient’s history, kidney function, allergies, and other health conditions.

These programs grew out of medication reconciliation efforts that became mandatory in U.S. hospitals after 2006. But it wasn’t until 2010-2012 that pharmacists began leading these efforts systematically. Today, 87% of U.S. academic medical centers and 63% of community hospitals have formal programs. They’re no longer optional-they’re standard practice in high-performing systems.

The goal? Reduce adverse drug events. Prevent unnecessary hospital visits. And stop patients from taking drugs that do more harm than good. In practice, that means stopping a proton pump inhibitor that’s been used for five years without a clear reason. Or switching a high-risk anticholinergic to a safer alternative for an elderly patient with dementia. These aren’t theoretical changes-they’re real, measurable interventions.

How These Programs Are Built and Run

Successful programs don’t rely on one person doing everything. They use teams. A typical setup includes one pharmacist and three to four medication history technicians. The technicians collect the patient’s full medication list-what they’re taking at home, what’s documented in old records, what’s been prescribed recently. The pharmacist reviews it all, spots discrepancies, and makes recommendations.

Here’s how it works in a hospital setting:

- Technicians interview patients and caregivers during admission, often before the doctor even sees them.

- They compare the patient’s reported list with the hospital’s electronic records.

- On average, they find 3.7 discrepancies per patient-missing meds, wrong doses, drugs that shouldn’t be there.

- The pharmacist reviews each discrepancy and decides: Is this a medication that needs to be stopped? Changed? Restarted?

- If a non-formulary drug is on the list, the pharmacist checks for a clinically appropriate substitute.

Studies show that with this model, 68.4% of non-formulary medications are successfully substituted at admission. That’s not luck-it’s a system. Training matters. Technicians need at least two hours of classroom instruction and five eight-hour supervised shifts before they work independently. After training, they complete medication histories with 92.3% accuracy.

Time is a big constraint. A full reconciliation takes about 67 minutes per patient. That’s why splitting tasks is key. Technicians handle data gathering. Pharmacists handle decision-making. This allows the team to scale-even in busy emergency departments or intensive care units.

Why Pharmacist-Led Programs Outperform Other Models

Some hospitals try to handle medication reconciliation with nurses or physicians alone. But research shows that’s not enough. A systematic review of 123 studies found that 89% of pharmacist-led programs reduced 30-day readmissions. Only 37% of non-pharmacy-led efforts did the same.

Why? Because pharmacists are the only clinicians trained specifically to understand drug interactions, pharmacokinetics, and therapeutic alternatives. Doctors focus on diagnosis and treatment plans. Nurses focus on monitoring and care delivery. Pharmacists focus on the medication itself.

Take high-risk patients-those over 65, taking five or more medications, or with poor health literacy. For them, pharmacist-led programs are game-changers. In one study, patients under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) saw a 22% greater drop in readmissions when a pharmacist was involved. The OPTIMIST trial showed that comprehensive pharmacist intervention cut 30-day readmissions by nearly 40% compared to medication review alone. The number needed to treat was just 12-that means for every 12 patients helped, one hospitalization was avoided.

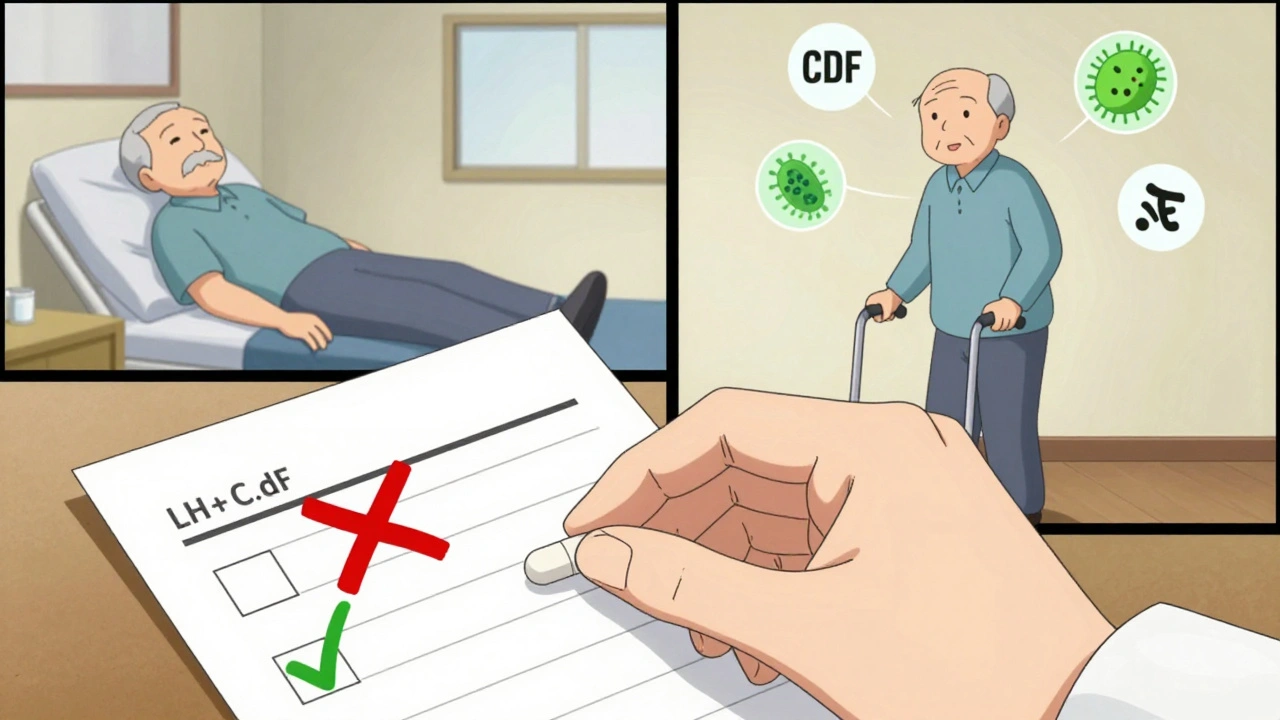

And it’s not just about keeping people out of the hospital. These programs reduce adverse drug events by 49%. That’s nearly half the number of dangerous reactions like internal bleeding, kidney failure, or dangerous drops in blood pressure. In one study, deprescribing anticholinergics in older adults led to a 41% reduction in falls. Stopping unnecessary proton pump inhibitors cut C. difficile infections by 29%.

Where These Programs Succeed-and Where They Struggle

Not every program works perfectly. One major barrier is physician resistance. In 43% of academic medical centers, doctors don’t accept pharmacist recommendations. Why? Sometimes it’s habit. Sometimes it’s lack of trust. Sometimes it’s just too busy to review another note.

Successful programs solve this by integrating directly into the electronic health record. When a pharmacist recommends a substitution, the system flags it for the prescriber with a clear rationale: “Patient on pantoprazole for 7 years without GI indication. Consider discontinuation. Risk of C. diff: high.” This isn’t a suggestion-it’s a clinical alert tied to evidence.

Another issue is deprescribing. Pharmacists often recommend stopping medications that are no longer needed. But physicians accept only about 30% of these suggestions. That’s changing. In skilled nursing facilities, deprescribing programs have grown from 18% adoption in 2020 to 42% in 2023. The key? Using standardized protocols. For example, the Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medications in older adults gives pharmacists a clear, evidence-based list to reference.

Time and staffing are also challenges. Sixty-eight percent of programs cite time as their biggest barrier. That’s why some hospitals use AI tools to speed up medication history collection. Pilots at 14 academic centers show AI reduces data entry time by 35%. That’s a game-changer for busy units.

And then there’s reimbursement. Only 32 states fully reimburse pharmacist-led substitution services through Medicaid. Medicare Part D covers medication therapy management for nearly 29 million beneficiaries, but the paperwork is so heavy that many pharmacists can’t keep up. The 2022 Consolidated Appropriations Act mandated medication reconciliation for all Medicare Advantage patients-a $420 million opportunity. But without clear billing codes and payment rates, most providers still can’t get paid for the work they do.

The Future: Integration, Expansion, and Policy Change

The future of pharmacist-led substitution programs isn’t just about hospitals anymore. They’re moving into post-acute care, home health, and even retail pharmacies. By 2023, 42% of skilled nursing homes had formal deprescribing programs. That number will keep rising as value-based care models take hold.

Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are now including pharmacist-led substitution metrics in their quality agreements. Sixty-three percent of ACOs track these programs as part of their performance targets. That means hospitals and clinics are being financially rewarded for reducing readmissions and adverse events-not just for treating them.

Regulatory changes are catching up. The 2024 CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Proposal includes specific documentation standards for pharmacist-led substitutions. If adopted, this could increase reimbursement rates by 18-22%. Twenty-seven state pharmacy associations are lobbying for expanded substitution authority, so pharmacists can make changes without needing a doctor’s signature in more cases.

Research is also narrowing in on high-risk drug categories. Anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, and long-term PPIs are now priority targets. Studies show clear, measurable benefits when pharmacists step in to stop them.

The biggest gap? Rural areas. Only 22% of critical access hospitals have full programs, compared to 89% in urban academic centers. Pharmacist shortages are the main reason. But telepharmacy and AI-assisted tools are starting to bridge that gap. In some states, pharmacists now remotely review medication lists for multiple rural clinics from a central hub.

What This Means for Patients and the System

At the end of the day, these programs aren’t about saving money for hospitals. They’re about keeping patients safe. A 30-day readmission isn’t just a statistic-it’s a person back in the ER because they took the wrong pill. A fall in a nursing home isn’t an accident-it’s often a side effect of a drug that shouldn’t have been there.

The data is clear: pharmacist-led substitution programs reduce adverse events by nearly half. They cut readmissions by 11% on average. They save between $1,200 and $3,500 per patient by preventing hospitalizations. And they’re backed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Joint Commission, and the American Pharmacists Association-all calling them essential.

This isn’t the future of pharmacy. It’s the present. And for patients caught in the gaps between care settings, it’s the difference between going home safely-and ending up back in the hospital.

Are pharmacist-led substitution programs only for hospitalized patients?

No. While they started in hospitals, these programs are now expanding into skilled nursing facilities, home health, and community pharmacies. In 2023, 42% of skilled nursing homes had formal deprescribing programs led by pharmacists. Community pharmacies are also starting to offer medication reviews for patients with complex regimens, especially those transitioning from hospital to home.

Do pharmacists need doctor approval to make substitutions?

It depends on state law and the setting. In most hospitals, pharmacists make recommendations, but physicians must sign off. In some states like Oregon, Washington, and California, pharmacists have expanded practice authority and can initiate substitutions for certain medications without a prescriber’s order-especially for chronic conditions like hypertension or diabetes. This is becoming more common as legislation evolves.

How do you know if a medication should be stopped?

Pharmacists use evidence-based tools like the Beers Criteria for older adults, STOPP/START guidelines, and clinical decision support systems built into electronic health records. They look for medications that are no longer indicated, duplicate therapies, drugs with high risk of side effects, or those that haven’t been reviewed in over a year. For example, a proton pump inhibitor prescribed five years ago for heartburn with no current symptoms is a prime candidate for deprescribing.

Can these programs really save money?

Yes. Studies show an average cost savings of $1,200 to $3,500 per patient by preventing hospital readmissions and avoiding expensive adverse drug events. Hospitals with these programs also face lower penalties under CMS’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. One analysis found that hospitals using pharmacist-led substitution saw 11.3% lower readmission penalties. The market for these services is projected to reach $3.24 billion by 2027.

Why aren’t these programs in every hospital?

The main barriers are staffing, reimbursement, and physician resistance. These programs require trained pharmacists and technicians, which is hard in rural or underfunded facilities. Reimbursement is inconsistent-only 32 states fully pay for these services through Medicaid. And some doctors don’t trust or prioritize pharmacist recommendations. But as evidence grows and regulations change, adoption is accelerating.

Been on the front lines of this in the UK NHS - the pharmacist-led med reviews are the only thing keeping elderly patients from getting crushed by polypharmacy. One guy had seven different anticholinergics on his list. Seven. He was falling every other week. We stopped four, switched two, and within a month he was walking his dog again. No magic, just clinical sense.

Technicians are the unsung heroes here. They’re the ones digging through old GP notes, calling family members at 7am, and catching the ‘oh yeah, I take that little blue pill every Tuesday’ meds that never made it into the system.

THIS. THIS IS WHAT HEALTHCARE SHOULD LOOK LIKE. Stop pretending doctors are the only ones who know what’s going on with meds. Pharmacists are the only ones trained to see the whole web of interactions - not just the one drug for the one symptom. And if your hospital doesn’t have this program, demand it. Your grandma’s life might depend on it.

I’ve seen nurses scramble to fix med errors because the docs were too busy. Pharmacists? They’re the ones who actually read the chart. They don’t just prescribe - they protect.

Love how this breaks down the team structure - techs doing the legwork, pharmacists making the calls. That’s smart workflow design. I’ve worked in a place where the pharmacist had to do both, and it was chaos. No way they could keep up with 30+ admissions a day.

Also, the 92.3% accuracy stat for trained techs? That’s wild. It’s not just about credentials - it’s about structure. Give people clear protocols and training, and they crush it. Why don’t we do this more often in healthcare?

And yeah, AI helping with data entry? Long overdue. I’ve seen pharmacists spend 40 minutes just typing in meds from a 12-page printout. That’s not clinical work - that’s data entry hell.

Medication is the silent war inside the body. We give pills like prayers - hoping they heal, fearing they destroy. The pharmacist, standing between the prescription and the person, is the priest of this sacred chaos.

Who are we, really, to trust a machine with our lives? Or a doctor too tired to see the whole picture?

The pharmacist sees the ghosts in the chart - the drugs that should be dead but still whisper in the system.

Okay but let’s be real - this whole ‘pharmacist-led’ thing is just a fancy way to say ‘we don’t trust doctors anymore.’

Next thing you know, pharmacists are writing prescriptions for antibiotics and antidepressants. Where does it end? Are we turning pharmacies into mini-clinics staffed by people who memorize drug interaction charts but can’t diagnose pneumonia?

I’ve seen pharmacists get it wrong too. One guy swapped out a beta-blocker for a calcium channel blocker because ‘it’s cheaper’ - didn’t check the patient had severe asthma. Dude ended up in the ICU. So yeah, ‘evidence-based’ doesn’t mean ‘foolproof.’

Pharmacist-led substitution programs are not optional. They are essential. The data is overwhelming. The outcomes are measurable. The cost savings are undeniable. The human impact is profound.

Every time a patient avoids a hospital readmission, every time a dangerous drug is deprescribed, every time a family is spared the trauma of a preventable adverse event - that is not just efficiency. That is dignity.

It is time for every healthcare system to adopt this model without delay. Not because it’s trendy. But because it is right.

Oh, here we go again - the ‘pharmacists are heroes’ narrative. Let’s not ignore the fact that most of these ‘substitutions’ are just cost-cutting in disguise.

Who benefits? The hospital. The insurer. Not the patient. You think they care if grandma’s on a PPI for five years? No. They care that it’s $30 cheaper to stop it.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘evidence.’ Beers Criteria? That’s a 20-year-old list with outdated assumptions. I’ve seen pharmacists yank meds that were still helping patients because it ‘looked bad’ on a report.

This isn’t patient care. It’s checkbox medicine.

Only 32 states reimburse this? That’s a national scandal. Pharmacists are the most underutilized clinicians in the entire system. We let them count pills but not make clinical decisions? We train them for six years and then treat them like glorified cashiers?

And don’t even mention the 43% of docs who ignore their recommendations. That’s not resistance - that’s arrogance. You think you’re the only one who knows what’s going on? You’re not. You’re just louder.

Stop treating pharmacy like a support role. It’s a frontline specialty. And if you’re still skeptical, go read the OPTIMIST trial again. Then shut up.

Just want to add - the real win here is the shift from reactive to proactive care. We used to wait for someone to have a GI bleed from an NSAID, then treat it. Now we stop the NSAID before it starts.

And the rural telepharmacy angle? Huge. My cousin in West Virginia gets her med review over video from a pharmacist in Omaha. She’s 82, has 9 meds, and never had to drive 90 miles to the clinic. That’s equity.

Yeah, docs need to get on board. But the system’s changing. And honestly? It’s about time.