When your heart beats, it follows a precise electrical pattern. On an ECG, that pattern shows up as waves - P, Q, R, S, T. The QT interval is the time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave. It’s the electrical reset phase of the heart’s lower chambers. When this interval gets too long - a condition called QT prolongation - your heart can slip into a dangerous rhythm called torsades de pointes. And it’s not rare. About 223 medications are currently flagged for this risk, according to crediblemeds.org. Many of them are common prescriptions you might never suspect.

What Exactly Is QT Prolongation?

QT prolongation isn’t a disease. It’s a warning sign on your ECG. It means your heart muscle is taking longer than it should to recharge between beats. That delay creates a perfect storm for a chaotic, life-threatening arrhythmia called torsades de pointes. This isn’t just a slow heartbeat - it’s a twisting, erratic rhythm that can turn into ventricular fibrillation and kill you in minutes.

The main culprit? Blockage of the hERG potassium channel. This channel, found in heart cells, lets potassium flow out to help the heart reset. When drugs block it - even slightly - the reset takes longer. That’s the QT interval stretching out. It’s not always obvious. Many people feel fine. No chest pain. No dizziness. Just a longer line on an ECG. But that line can be deadly.

Doctors use a number called QTc - the corrected QT interval - to account for heart rate. The cutoff for concern? 500 milliseconds. If your QTc hits that mark, or jumps more than 60 ms from your baseline, the risk of torsades spikes 3 to 5 times. Women are at higher risk - about 70% of documented cases are in women, especially after childbirth or in older age.

Drugs That Directly Cause QT Prolongation

Not all drugs that prolong QT are dangerous. Some are designed to do it - like sotalol and amiodarone, used to treat dangerous arrhythmias. But even these carry risk. Sotalol causes torsades in 2-5% of patients. Amiodarone? Lower risk, around 0.7-3%, because it blocks multiple channels, not just hERG.

But the bigger problem? Non-heart drugs you’d never think of.

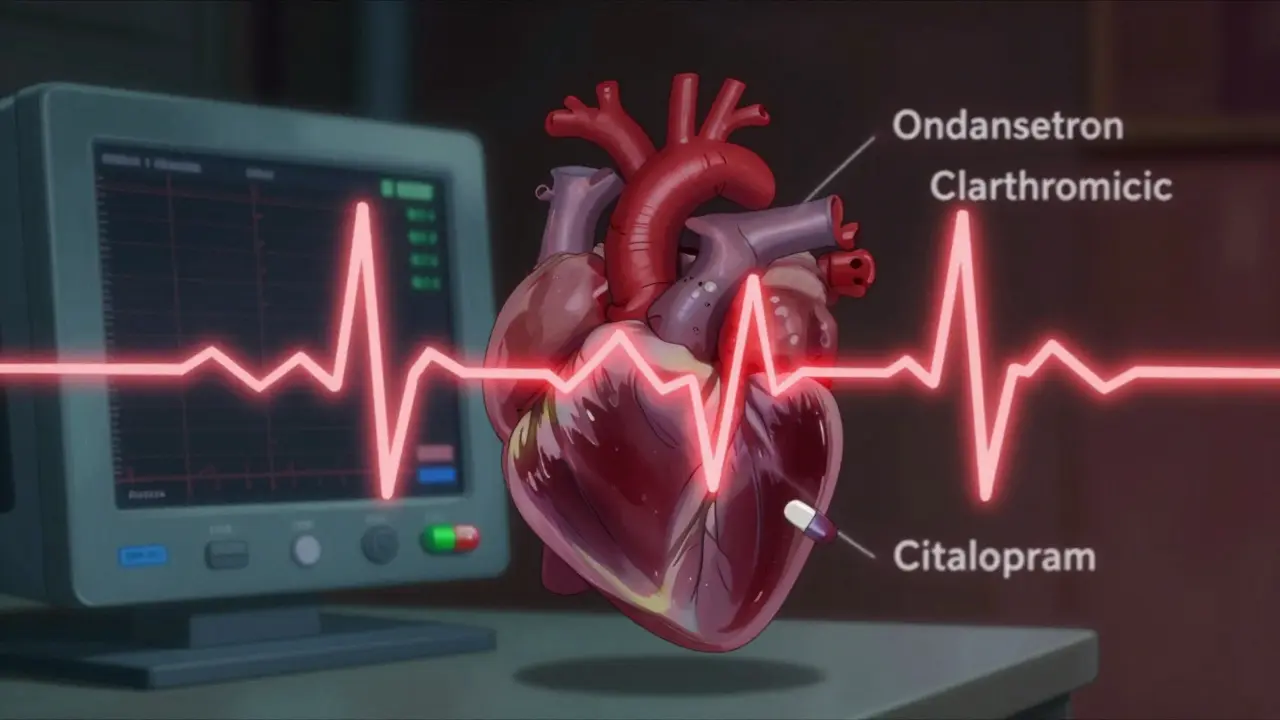

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin and clarithromycin (macrolides) can prolong QT by 15-25 ms. Moxifloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) adds 6-10 ms. Avoid them with other QT drugs.

- Antifungals: Fluconazole, especially at high doses (400 mg+), is a known risk.

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol, ziprasidone, and thioridazine carry black box warnings. Ziprasidone’s label explicitly warns of sudden cardiac death risk.

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (Zofran) is one of the most common triggers in ER cases. One study found it involved in 42% of reported torsades cases.

- Antidepressants: Citalopram and escitalopram cause dose-dependent QT prolongation. The FDA capped citalopram at 40 mg daily (20 mg if over 60) because of this.

- Opioid replacement: Methadone is a silent killer. Doses over 100 mg/day significantly raise risk. Many patients on maintenance therapy have QTc >470 ms - but with monitoring, most stay safe.

Here’s the catch: these drugs are often prescribed alone. The real danger comes when they’re stacked.

Combination Risks: The Silent Killer

One QT-prolonging drug? Low risk. Two or three? Risk jumps dramatically.

A 2020 FDA analysis of 147 torsades cases found 68% involved two or more QT-prolonging drugs. The most dangerous combos? Ondansetron + azithromycin. Haloperidol + ondansetron. Citalopram + clarithromycin.

Why? These drugs don’t just add up - they multiply. Azithromycin slows how fast your liver breaks down ondansetron. That means more ondansetron in your blood. More hERG blockage. More QT prolongation. A patient with a normal QTc of 440 ms can jump to 530 ms in under 24 hours.

Even common OTC meds can play a role. Antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can prolong QT at high doses. And if you’re taking it with an antibiotic? You’re playing Russian roulette with your heart.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about you.

- Women: Hormonal differences make their hearts more sensitive to hERG blockade. Postpartum women are especially vulnerable.

- Older adults: Slower metabolism, more meds, weaker kidneys - all raise drug levels.

- People with heart disease: Scarred tissue, low ejection fraction, prior arrhythmias - all make the heart more excitable.

- Those with low potassium or magnesium: Electrolytes help the heart reset. Low levels make QT prolongation worse.

- People with genetic risk: About 30% of drug-induced torsades cases happen in people with subtle hERG gene mutations they didn’t know they had.

One 65-year-old woman on citalopram and clarithromycin for a sinus infection? Her QTc jumped from 450 to 540 ms. She collapsed in the pharmacy. She survived - barely. That’s not a rare story.

How Do Doctors Manage This Risk?

Good clinicians don’t guess. They follow a system.

- Screen before prescribing: Check for electrolyte imbalances, kidney/liver disease, and other QT drugs.

- Do a baseline ECG: For anyone starting high-risk meds - especially if over 65, female, or on multiple drugs.

- Repeat ECG in 3-7 days: That’s when drug levels peak. If QTc >500 ms or increased >60 ms, stop the drug unless there’s no alternative.

- Use crediblemeds.org: It’s the gold standard. It lists drugs as ‘Known Risk,’ ‘Possible Risk,’ or ‘Conditional Risk’ - with clear guidance.

Hospitals that use electronic alerts tied to EHR systems cut dangerous prescribing by 58%. That’s not a small win. That’s lives saved.

What About Newer Drugs?

The risk isn’t going away. In fact, it’s growing.

Obesity drugs like retatrutide, approved in late 2023, showed QTc prolongation of 8.2 ms in trials. Cancer drugs? Of the 27 tyrosine kinase inhibitors approved by 2024, 12 carry QT prolongation warnings. That’s nearly half.

Why? These drugs are complex. They hit multiple targets. One might help fight cancer. Another might block hERG. The trade-off is real.

The industry is responding. The CiPA initiative - launched by the FDA, EMA, and Japan’s PMDA - now requires new drugs to be tested on multiple ion channels, not just QT interval. It’s more accurate. But it’s also more expensive. About 15% more drug candidates are failing in development because of cardiac safety concerns.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on any of these meds - especially more than one - don’t panic. But do act.

- Ask your doctor: ‘Could this drug affect my QT interval?’

- Ask: ‘Am I on another drug that could make this worse?’

- Get an ECG before starting - especially if you’re over 60, female, or have heart issues.

- Don’t take OTC meds like Benadryl or antacids with QT drugs without checking.

- If you feel lightheaded, dizzy, or have palpitations after starting a new drug - get help. Don’t wait.

QT prolongation isn’t something you can feel. But it’s something you can prevent. With awareness, with questions, and with a simple ECG, you can avoid a silent, sudden death.

Bottom Line

QT prolongation is a hidden danger in everyday prescriptions. It’s not about avoiding meds. It’s about knowing which ones are risky - and when they’re stacked together. The drugs that cause it aren’t obscure. They’re common. The risk isn’t rare. It’s documented. And the fix? Simple: check your ECG, know your meds, and ask the right questions.

One ECG. One conversation. Could be the difference between walking out of the hospital - and not walking out at all.

Can a normal ECG rule out risk of QT prolongation?

No. A normal ECG today doesn’t mean you’re safe tomorrow. QT prolongation can develop after starting a new drug or changing a dose. That’s why doctors recommend a baseline ECG before starting high-risk meds and a repeat one 3-7 days later. Even if your first ECG is normal, you still need follow-up if you’re on drugs like sotalol, citalopram, or ondansetron.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

Not always. Mild prolongation (QTc 450-499 ms) in a healthy person on one drug carries very low risk. But once QTc hits 500 ms or increases more than 60 ms from baseline, the risk of torsades de pointes rises sharply. The danger isn’t the number alone - it’s the combination with other risk factors like female sex, low potassium, or multiple QT drugs.

Can I take over-the-counter meds if I’m on a QT-prolonging drug?

Be careful. Common OTC drugs like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), cimetidine (Tagamet), and some antacids can also prolong QT - especially in higher doses or with kidney problems. Even natural supplements like licorice root can lower potassium. Always check with your pharmacist before adding anything new, even if it’s ‘just a pill for allergies.’

Are there safer alternatives to QT-prolonging drugs?

Yes, often. For nausea, metoclopramide is a QT-safe alternative to ondansetron. For depression, sertraline or citalopram (at low doses) are safer than escitalopram or fluoxetine. For infections, azithromycin can be swapped for amoxicillin if appropriate. But it’s not always simple - your doctor must weigh risks and benefits. Never switch meds on your own.

How often should I get my QT interval checked?

For high-risk drugs - like sotalol, methadone, or citalopram - get a baseline ECG before starting. Then repeat it 3-7 days after starting or after any dose increase. If your QTc stays below 500 ms and you have no symptoms, you may only need yearly checks. But if you’re on multiple QT drugs or have heart disease, your doctor may recommend more frequent monitoring.

Just got prescribed Zofran for morning sickness and had no idea it could mess with my heart 😳 I’m gonna ask my doc for an ECG before I even fill it. Better safe than sorry!

My grandma’s on methadone and citalopram - she’s 72, female, and has kidney issues. Her cardiologist caught her QTc at 510 after a routine check. They switched her to sertraline and now she’s fine. This post saved her life, honestly.

Ugh. Another ‘medical scare’ post. People are so hypochondriacal these days. If you’re not dying from a heart attack, stop obsessing over a line on a graph. I’ve taken Zofran three times and I’m still standing. Also, who even checks QT intervals anymore? It’s 2024, not 1998.

In India, doctors rarely check ECGs before prescribing antibiotics or antifungals. I saw a 58-year-old woman collapse at a pharmacy after taking clarithromycin + Benadryl for a cold. No one asked about her meds. No one checked her heart. This is why so many die silently here. We need awareness, not just lists.

Thank you for this. My mom’s on amiodarone and started taking fluconazole for a yeast infection. Her doctor didn’t warn her - I had to Google it and demand an ECG. She was at 505 ms. They changed the antifungal immediately. I’m so glad I found this. Sharing it with everyone I know.

Okay, real talk - if you’re on more than one of these meds, you’re playing Jenga with your heart. And guess what? The pharmacy doesn’t warn you. Your doctor’s rushing. The system’s broken. But you? You can be the hero. Ask the question. Get the ECG. Don’t wait until you’re on the floor. Your future self will high-five you.

So... we're now treating every minor prescription like it's a nuclear bomb? What's next? 'Warning: Ibuprofen may cause existential dread in susceptible individuals'? This is fear-mongering dressed up as medicine. People are dying from anxiety over ECGs, not torsades.

If you’re taking OTC meds with prescription drugs, you’re already irresponsible. No one’s forcing you to take Benadryl with your antidepressant. It’s basic pharmacology. Stop acting like this is some conspiracy. It’s common sense. And if you don’t know your meds, maybe you shouldn’t be self-medicating.

It’s funny how we’ve turned medicine into a game of Russian roulette with side effects. But here’s the deeper truth: we’ve outsourced our health to algorithms and pill bottles. We don’t ask questions because we’ve been trained to trust the system. But the system doesn’t care about your QT interval - it cares about profit margins. The real risk isn’t the drug. It’s the silence we’ve been conditioned to accept.