When a generic drug company wants to bring a new version of a popular medication to market, they don’t need to run another full clinical trial. Instead, they run a bioequivalence (BE) study - a focused, smaller trial that proves their version behaves the same way in the body as the original brand-name drug. But here’s the catch: if the statistics are wrong, the whole study fails. And failing a BE study isn’t just embarrassing - it costs millions and delays patient access to affordable medicine.

The core of every BE study isn’t the drug itself, but the numbers. Specifically, two things: power and sample size. Get these right, and you have a study that can detect true equivalence. Get them wrong, and you’ll either waste money on too many participants or - worse - miss a real difference because your study was too small.

Why Power and Sample Size Matter More Than You Think

Most people think of clinical trials as tests to see if a drug works better than a placebo. BE studies are different. They’re not looking for superiority. They’re looking for equivalence. That means the test drug’s absorption rate and concentration in the blood must be very close to the reference drug - within a narrow range.

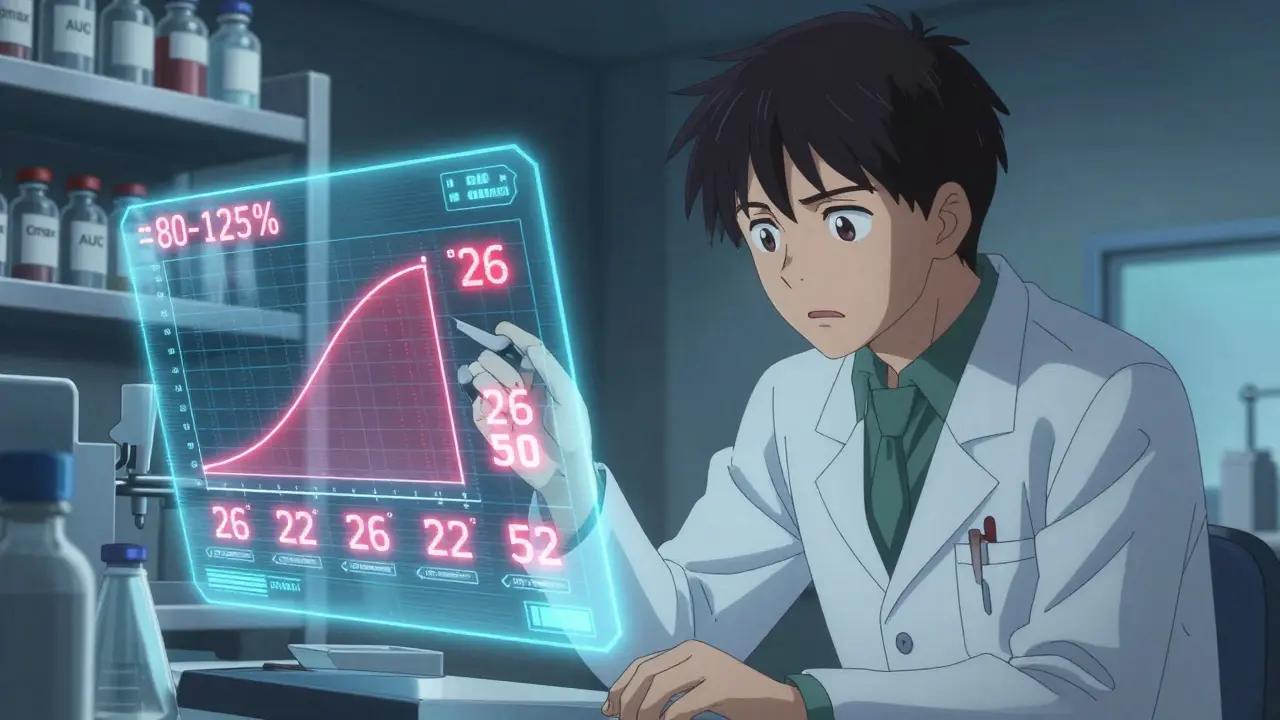

Regulators like the FDA and EMA say that range is 80% to 125% for the geometric mean ratio of key measurements: Cmax (peak concentration) and AUC (total exposure). If the 90% confidence interval of that ratio falls entirely inside those bounds, the drugs are considered bioequivalent.

But how do you know you’ve tested enough people to be sure? That’s where power comes in. Power is the probability your study will correctly show equivalence if the drugs really are equivalent. The standard target is 80% or 90%. That means if you ran this same study 100 times, you’d get it right 80 or 90 times.

Low power means a high chance of a false negative - concluding the drugs aren’t equivalent when they actually are. That’s a disaster. It leads to rejected applications, delays, and lost revenue. A 2021 FDA report found that 22% of Complete Response Letters for generic drugs cited inadequate sample size or power calculations as the main issue.

What Drives Sample Size in a BE Study?

Sample size isn’t pulled out of thin air. It’s calculated using four key inputs:

- Within-subject coefficient of variation (CV%) - This measures how much a person’s own response to the drug varies between doses. Some drugs are very consistent - think of a simple tablet with high solubility. Others, like blood thinners or cancer drugs, swing wildly between doses. CV% can range from 10% to over 40%. The higher the CV, the more people you need.

- Expected geometric mean ratio (GMR) - This is your best guess at how the test drug compares to the reference. Most generic manufacturers assume 0.95 to 1.05. But if you assume a perfect 1.00 ratio and the real ratio is 0.95, your sample size estimate could be 32% too low.

- Equivalence margins - Usually 80-125%, but sometimes widened for highly variable drugs under special rules (RSABE).

- Target power - 80% is common, but the FDA often expects 90% for narrow therapeutic index drugs (like warfarin or lithium).

Here’s a real example: For a drug with a 20% CV, a GMR of 0.95, and 80% power, you’d need about 26 subjects in a crossover design. But if the CV jumps to 30%? You need 52. Double the variability, double the subjects. That’s why pilot data matters.

Many companies rely on published literature for CV estimates. Bad idea. The FDA reviewed 147 BE submissions and found that literature-based CVs underestimated true variability by 5-8 percentage points in 63% of cases. That’s like planning a road trip with a map that says the highway is 200 miles - when it’s actually 240. You’ll run out of gas.

How to Calculate Sample Size - The Basics

The math behind sample size for BE studies looks intimidating, but it’s built on a simple principle: more variability = more people needed. The formula used by statisticians looks like this:

N = 2 × (σ² × (Z₁₋α + Z₁₋β)²) / (ln(θ₁) - ln(μₜ/μᵣ))²

Don’t panic. You don’t need to memorize it. You need to understand what goes in:

- σ² = within-subject variance (derived from CV%)

- Z₁₋α and Z₁₋β = statistical constants for alpha (0.05) and power (0.80 or 0.90)

- θ₁ = lower equivalence limit (0.80)

- μₜ/μᵣ = expected test/reference ratio (e.g., 0.95)

Most teams use software to do the math. Tools like PASS, nQuery, and FARTSSIE are built specifically for BE studies. They let you plug in your CV, GMR, and power, and instantly get a sample size. Industry professionals say 78% use these tools iteratively - tweaking inputs to see how changes affect the number of subjects needed.

What About Dropouts?

No study is perfect. People drop out. They get sick. They move. They change their mind.

That’s why you always add a buffer. The standard recommendation is to increase your calculated sample size by 10-15%. So if your math says 26 subjects, plan for 30. If it says 52, plan for 60. Skipping this step is one of the most common reasons studies fail after they’ve already started.

EMA rejected 29% of BE studies in 2022 for failing to account for sequence effects or dropouts properly. That’s not just bad stats - it’s poor planning.

Highly Variable Drugs: The RSABE Escape Hatch

Some drugs are naturally all over the place. Think of drugs with poor solubility or those metabolized by enzymes that vary widely between people. For these, traditional BE rules can demand 100+ subjects - which is unethical and impractical.

That’s where Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) comes in. Instead of a fixed 80-125% range, RSABE widens the acceptance limits based on how variable the reference drug is. If the CV is above 30%, you get more room.

For example, a drug with a 45% CV might only need 24-48 subjects under RSABE instead of 100+. The FDA allows this for certain drugs. The EMA has similar rules. But here’s the catch: you must prove the drug is highly variable in the first place - using pilot data or published studies. And you can’t use RSABE for all drugs. It’s only for those with proven high variability.

Don’t Forget Both Endpoints: Cmax and AUC

BE studies measure two things: Cmax and AUC. Each tells a different story. Cmax shows how fast the drug gets into your blood. AUC shows how much total drug you’re exposed to over time.

Most teams focus on the parameter with the higher CV - usually Cmax. But regulators expect you to show equivalence for both. If you only calculate power for Cmax and assume AUC will follow, you’re risking failure.

Simulations published in Pharmaceutical Statistics show that ignoring the joint power for both endpoints reduces effective power by 5-10%. That’s like flipping a coin twice and only checking one side. The American Statistical Association recommends calculating joint power - but only 45% of generic sponsors actually do it.

Software, Documentation, and Regulatory Traps

Using the right tool isn’t enough. You have to document everything.

The FDA’s 2022 Bioequivalence Review Template says your submission must include:

- Software name and version used

- Exact input values (CV%, GMR, power, margins)

- Justification for those values (e.g., “CV was taken from a pilot study of 18 subjects”)

- Dropout adjustment applied

In 2021, 18% of statistical deficiencies in generic drug submissions were due to incomplete documentation. Regulators don’t just want the number - they want to see your logic.

And don’t assume your CRO (contract research organization) knows what they’re doing. In 2022, the FDA issued a warning letter to a major CRO for underestimating required sample size by 25-35% due to flawed power calculations. That’s not a minor mistake. That’s a systemic failure.

The Future: Model-Informed Bioequivalence

There’s a new wave coming. Model-informed bioequivalence (MIBE) uses advanced statistical modeling - like population pharmacokinetics - to predict drug behavior with fewer subjects. Early results show it can cut sample sizes by 30-50% for complex products like inhalers or extended-release tablets.

The FDA’s 2022 Strategic Plan for Regulatory Science supports MIBE. But as of 2023, only 5% of BE submissions use it. Why? Regulatory uncertainty. Most reviewers aren’t trained to evaluate these models. Companies are hesitant to risk rejection.

For now, stick with the proven methods. But keep an eye on MIBE. It’s the future - and early adopters will have a big advantage.

Final Checklist for a Robust BE Study Design

Before you enroll a single participant, run through this:

- ✅ Use pilot data, not literature, for CV% estimates

- ✅ Assume a realistic GMR (0.95-1.05), not 1.00

- ✅ Calculate power for both Cmax and AUC together

- ✅ Use regulatory-approved software (PASS, nQuery, FARTSSIE)

- ✅ Add 10-15% buffer for dropouts

- ✅ Document every assumption and input

- ✅ For CV > 30%, evaluate if RSABE applies

- ✅ Confirm power target matches regulator expectations (80% vs. 90%)

There’s no magic number. But if you follow these steps, you won’t be one of the 22% whose study gets rejected for poor power analysis.

What is the minimum sample size for a bioequivalence study?

The minimum sample size depends on the drug’s variability. For a low-variability drug (CV < 10%) with 80% power, you might need as few as 12-18 subjects. For moderate variability (CV ~20%), 24-30 is typical. For highly variable drugs (CV > 30%) without RSABE, you may need 60 or more. Always calculate based on real data - never guess.

Is 80% power enough for a BE study?

80% power is the regulatory minimum accepted by the EMA and often used in practice. But the FDA expects 90% power for narrow therapeutic index drugs (like digoxin or cyclosporine). If you’re submitting globally, aim for 90% to avoid delays. For routine generics, 80% is acceptable - but only if you document your rationale.

Can I use a parallel design instead of crossover for BE studies?

Crossover designs are preferred because they reduce variability by using each subject as their own control. Parallel designs require roughly double the sample size because they can’t control for individual differences. Use parallel only if the drug has a long half-life (making crossover impractical) or if it causes irreversible effects. Most BE studies use crossover for efficiency.

Why do some BE studies fail even with large sample sizes?

Large sample sizes don’t fix bad design. Common reasons include: using the wrong CV estimate, assuming a perfect 1.00 GMR, not adjusting for dropouts, or failing to account for sequence effects in crossover studies. Sometimes, the drug formulation itself isn’t bioequivalent - no amount of subjects can fix that. Power analysis ensures you can detect equivalence - but it doesn’t create it.

What’s the difference between CV% and GMR?

CV% (coefficient of variation) measures how much a person’s response to the drug varies between doses - it’s about consistency. GMR (geometric mean ratio) compares the average exposure of the test drug to the reference drug - it’s about relative performance. High CV% means you need more people. A GMR far from 1.00 means the drugs behave differently - which could mean they’re not bioequivalent.

Do I need a biostatistician to run a BE study?

Yes. BE study design involves complex statistical assumptions and regulatory-specific rules. Even experienced pharmacologists often rely on biostatisticians to run power calculations and validate methods. The Northwestern University Applied Statistics guidance recommends this collaboration as standard practice. Skipping this step increases your risk of regulatory rejection.

Next Steps: What to Do Now

If you’re planning a BE study:

- Start with pilot data - even 12-18 subjects can give you a reliable CV estimate.

- Use ClinCalc or PASS to run your sample size calculation with realistic inputs.

- Double-check your assumptions: Is your GMR too optimistic? Did you forget AUC?

- Add your dropout buffer.

- Document everything - not just the number, but why you chose it.

- Review the latest FDA/EMA guidelines - don’t rely on old templates.

There’s no shortcut to a solid BE study. But with the right approach, you can avoid the most common pitfalls - and get your generic drug to patients faster.

Wow, this is such a clear breakdown! 🙌 I’ve seen so many teams skip pilot data and just grab CVs from papers - and then wonder why their study fails. Seriously, don’t be that person. Pilot data isn’t optional, it’s your lifeline. Also, 10-15% buffer for dropouts? YES. Always. 😊

Yeah, I’ve been on both sides of this. Used to think 24 subjects was enough for everything. Then we got slapped by the FDA for not accounting for AUC power. Oof. Now I double-check everything. Don’t be like me before.

Let me just say this: if your CRO is using Excel to calculate sample size, fire them. 🚨 PASS, nQuery, or FARTSSIE - pick one and stick with it. I’ve seen so many submissions get rejected because someone typed in a CV of 18% when the pilot showed 27%. It’s not a typo, it’s negligence. And yes, I’ve had to clean up these messes. Don’t make me cry again.

RSABE is a game changer for crazy-variable drugs. We used it for a topical gel with 42% CV and cut our sample size from 110 to 38. Saved us like $2M. But yeah, you gotta prove the variability first - no guessing. FDA wants data, not vibes.

They’re all lying. The FDA doesn’t care about power. They just want to delay generics so Big Pharma can keep charging $500 for a pill. They invented CV% to confuse people. You think they want you to succeed? No. They want you to fail. And then they’ll sell you their ‘approved’ software for $50k.

For RSABE, the scaling factor is derived from the within-subject SD of the reference, computed as sWR = sqrt(MSEWR), where MSEWR is the mean squared error from the ANOVA of the reference treatment in a replicate design. The scaled limits are then: L = 80.00% × exp(0.76 × sWR), U = 100% / L, with a cap at 50% CV. Ensure your replicate design meets the minimum 12 subjects per sequence for regulatory acceptance.

Ugh, I read this whole thing. Like, why does it feel like a textbook? Can’t we just… do the thing? 😴 Also, who even uses FARTSSIE? Sounds like a typo.

While the author presents a superficially coherent framework for bioequivalence study design, it is fundamentally flawed in its implicit assumption that statistical power can be decoupled from clinical relevance. The 80-125% acceptance range, codified by regulatory fiat, lacks biological justification. One must question whether the pursuit of mathematical equivalence, divorced from pharmacodynamic congruence, constitutes a valid scientific endeavor. This entire paradigm is a regulatory construct masquerading as science.

just a quick note - i think u meant to say "GMR of 0.95" not "0.95 to 1.05" in the example, since GMR is a ratio, not a range. also, dropout buffer should be 15% max, not 10-15% - 10% is too risky. and yeah, crossover design is king unless the drug’s half-life is like 2 weeks. ty for the post though, super helpful!